Article: Alexandra Hakim: Jewellery as Conversation

Alexandra Hakim: Jewellery as Conversation

Meagan Day O’Rourke is a freelance writer who’s work includes profiles of artists and makers. Currently based in Madrid, Spain she can also be found in her hometown at the foot of the Rocky Mountains. “I’m a believer in beauty for beauty’s sake, though I’m becoming more and more interested in the intersection of art and politics, which Alexandra Hakim does so well. Rather than distract from the quality of her art, Hakim’s political commentary is the alchemy of her most beloved collections, inviting us into the story as participants. I was curious to know more about how she viewed the dynamic between the jewellery and the one who wears it — what she believed made jewellery meaningful, if anything.”

“My grandmother always had the most magnificent jewellery,” she tells me, sitting at the only table outside a neighbourhood coffee shop in Madrid, Spain. “To this day I’m inspired by the smells, the tastes and the textures from her house in the mountains of Lebanon.” Inspiration that is very much at the heart of the luxury jewellery brand that shares her name, Alexandra Hakim.

Hakim grew up in the UK. Her parents - both originally from Lebanon - moved to London before she was born. Her father, a surgeon by trade, kept a small studio upstairs for sculpting with clay. “I used to love just staying there with him while he did his work,” taking left over pieces of clay and moulding them into something of her own design. She knew she wanted to be a designer from a young age. Though she didn’t know jewellery design was a career option at that point, she knew she wanted to make “something tangible, something that could be worn, something empowering.”

“I’m Lebanese—” she tells me. “And usually you’re expected to be a doctor or a lawyer or something of the sort, but my parents were very supportive of me going into design, as long as I got into one of the top schools.” Hakim started her studies at Central Saint Martins in London, one of the world’s leading schools for art and design, touting alumni such as Alexander McQueen and Stella McCartney.

After completing a one-year-intensive program that allowed her to try a bit of everything —from fashion to fine art to architecture— she continued at Saint Martins pursing her undergrad in jewellery design. “I tried a metal workshop, and that’s when I realised, wow, this is what I want to do. I liked the gravitas of the metal. I like that it can be melted down over and over. I like that mistakes are more a part of the design process, more inspiring than they are anything else.” So she started experimenting with the medium— creating large scale sculptures, even remaking prosthetic limbs in the form of jewellery. But as she progressed, she found the learning environment oppressively competitive if not outright sabotaging. “My teacher, a famous dutch artist, told me my idea was terrible and then went on to open his exhibition with it,” she tells me, followed by a story about her sketchbook being stollen just before an important interview. “I knew I wanted something different after that,” she says.

So she applied to Rhode Island School of Design —a highly selective private school in Providence, Rhode Island— without telling anybody until she was accepted on a scholarship. “I went from this unhappy, super competitive place to this Disney World of artists.” Surrounded by supportive peers and inspiring teachers from all over the world, Hakim had found the place her creativity could thrive. “It was the kind of place where none of your friends go to bed, until everyone’s finished their work.”

Her first class was on metal smithing. With nothing but a block of brass in front of her, the teacher said, here’s a hammer and here’s a blowtorch, now make a spoon. The idea being, if you can make a spoon you can make anything. “I loved how old the techniques were, going back to antiquity to make these modern or contemporary products.”

Her second assignment, called “The Power of Suggestion”, was to create something that insinuated a colour, without using the colour. She took it a step further. “The jewellery making process in itself is so intricate and so fascinating to me. I tried to find my own way to produce something that evoked the process within the piece as well. In making jewellery, you use fire - you use a lot of heat - to burn and melt the metal in order to manipulate it. So what better than a matchstick, which is a very analog type of product that you use to create a flame, but then once it's consumed, every matchstick is completely different. They’re all so fragile and different and beautiful in their own way.” So instead of discarding them as waste from the jewellery making process, she kept them and turned them into jewellery. “Thats how I came up with my first collection, Pyromania. Because at the time, I felt like I was obsessed with fire.” That was the first pair of earrings she had ever made, and it remains one of her most popular collections.

The power of suggestion continues to be the alchemy of Alexandra Hakim designs. Signature collections feature handmade, one-of-a-kind, zero waste pieces, often created by casting seemingly insignificant objects into precious metals- turning them into luxury jewellery, ethically and sustainably made. As if to say, this matters. This is significant. Look at it.

While completing her studies, Hakim spent her summers interning for several world-renowned French design houses, including Van Cleef and Boucheron. “I really thought I wanted to work for a big house, I never imagined myself as a business owner. I wanted to be hired to design.” But by the time she graduated, her designs took a more innovative direction.

“On the surface [jewellery] can be such a luxury thing, which I was really having trouble with internally, struggling with like, I want to be able to make a difference, but can I do that through jewellery?” Can luxury jewellery have a positive impact? When she was approached by the Harvard medical startup Emulate to design pieces made for wearable medical chips, it was the perfect fit. “It was really such a great experience. Meanwhile, I was wearing the jewellery I had made back at design school and everywhere I would travel people would ask me ‘where did you get that, where can I buy it?’. So along the way, I was encouraged to start my own brand.” Using the money she was making from her job at Emulate, she was able to build her namesake brand on the side, in what she describes as “a very organic process”. First through Instagram, friends and family, and later expanding into an e-commerce platform. After about 4 years of working full time and developing her personal brand on nights and weekends, she went all in. “I decided to fully focus on my brand. That’s when things started to evolve, started to get real.”

Though she had previously been splitting time between Boston and London, when it came time to find a home for her own brand, she felt pulled to settle back in the place of her treasured childhood memories, Lebanon. While visiting in 2016, she met her now husband, and began building her brand — and her family— in the place of her roots.

“All the memories from my grandmother’s house came flooding back,” from the cane-weaved chairs on the balcony to the pistachio shells left in the ashtrays. “Its called khaizaran in Arabic,” she says, referring to the cane- weaving. “Once they rip or break you can’t do anything; you can’t fix them. So, I was like, let's do something with them. Let's turn them into something timeless. I went around collecting these old ripped up chairs that were no longer being used and turned them into a full collection.” Khaizaran is a collection of luxury jewellery featuring gold and silver bracelets, rings, earrings and a choker necklace all created using the original repurposed materials of the cane-woven chairs. “I realised that what I’m actually doing is recreating the nostalgia of this old Lebanese living space, where the family comes together. The pine trees and the shadow of the khaizaran chairs on the floor. I thought, I want to recreate these shadows and make them last forever. Pistachio shells, I would recycle them and turn them into pendants. I just wanted to embrace the Lebanese culture that I had kinda been far from, but that still held such a big place in my heart, and had ever since I can remember.”

This matters. This is significant. Look at it.

“At that point in time, my grandmother had passed away. I think that kind of pushed me to keep her memory alive. Also, the craft alive.” Craftsmanship in Lebanon has been passed down from generation to generation through the millennia. Luxury jewellery specifically, holds a rich history in the area that used to be Phoenicia, incorporating and innovating upon ancient techniques. “If you go to the various districts where these things are made, the craftsmen are very old and their children have kind of moved on you know, they live in a different century and they don’t have to take over their parents’ jobs. So, we’re losing a lot of the tradition, the craftsmanship. The heritage is being lost.” Hakim was inspired to see what she could do to keep the craft relevant or make it interesting again. “I realised that if I can make craftsmanship relevant in a way that will make people look twice at it today, maybe I can do that for the fisherman and the farmers, too.”

Her collection No More Fish in the Sea, inspired by a local fisherman dealing with the effects of water pollution, does just that. “I spent a day on a fisherman’s boat in Lebanon. He was just telling me his life’s story, he was saying ’10 years ago I caught so many fish I didn’t know what to do with them. That’s how I made a living. Now most of what I catch is rubbish.’ So I said, give me your rubbish.” The collection includes unique one-of-a-kind pieces such as industrial tuna fishing hooks transformed into luxury gold earrings embellished with freshwater pearls, as well as a textured gold necklace made from repurposed fishing materials and finished with natural pearls. “So, it's almost like a partnership between me and somebody who wants to have their voice heard or tell their story or just raise awareness in general.” Hakim tells me her aim with the collection was to bring awareness to the effects of pollution, “especially in a place like Lebanon with all the oil spills and water pollution and political tension in the area - the sea that was once crystal clear, you can’t even swim in it anymore.” What stands out most to me is the way she’s chosen to spotlight the issue by focusing on the people most effected by it, the workers, the tradesman - the ones who have their hands in it, day in and day out.

Putting people at the centre of her designs is a thread that carries throughout her collections. “I’m very inspired by farmers markets for example. Farmers are the base of civilisation in a way. If there are no farmers, we don’t eat. So I really wanted to put them at the forefront and give them the recognition that they deserve in the way that I know how to.” Her Berry collection features pieces such as silver earrings made from lemons, tomato plant stems turned into statement gold earrings, and a silver strawberry necklace with a leaf on the clasp— all made from produce you can find in the mountains and valleys of Lebanon. “I wanted to bring them together to give this taste of what the land has to offer, but also what these farmers do.”

The power of suggestion. This matters. This is significant. Look at it.

In 2019, the political and economic climate in Lebanon was quickly deteriorating; it was time to leave. Hakim and her husband moved to Madrid, Spain. “It was a bit disorienting.” Having built her brand, not only in, but around the country she loves, she would have to start again. And then Covid happened, bringing everything to a halt. “I learned that I’m somebody who has to work with their hands every day. It's what I do, it's what I love — it was a very difficult time, not having that.”

A year later, in the summer of 2020, Hakim had returned to visit Lebanon, when the explosion happened at the port in Beirut, leaving hundreds of thousands people dead, injured, or homeless overnight. “The whole country was effected. We had a lot of friends and family who were severely injured, lost their homes or their loves ones. We were lucky. We were still alive. It really put things into perspective, and helped me realise that maybe it's a blessing [to have moved], and I’m just gonna have to figure it out and start again, whatever that means.”

Sitting outside the cafe, ice melting in the bottom of our cups, I wonder if Hakim has all along been finding and salvaging pieces of the Lebanon she calls home, casting them in precious metals and jewels to make sure they aren't lost amongst the piles of rubble in a land devastated by decades of destruction. Is a part of her art to keep Lebanon itself alive— or at the very least, remembered? Highlighting the voices of the people, the land, the sea, and the beauty all at risk of losing their place in the story of a small country on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean.

In 2021, Hakim welcomed her first baby, “which was obviously the most love I’d ever felt,” she says with a pause, “but it did come with hardships.” For the first time in our conversation, I sense she is uneasy. “I didn’t feel like I could design anything new, I didn’t feel like I had the headspace to make something. I was just trying to treasure the moments I had with my baby and focusing all my energy into being a mother.” She tried designing a few collections, but didn’t feel inspired by them. “There was a lot of like, trying. I thought about shutting down the company so many times. I was losing money. But something kept telling me not to give up.”

Trying to find her footing in a new country, in the aftermath of a global pandemic, and the early days of motherhood, she tells me that for a long time she felt everything around her was falling apart, except the baby. “I was protecting her and she was protecting me. It was the only thing keeping me going.”

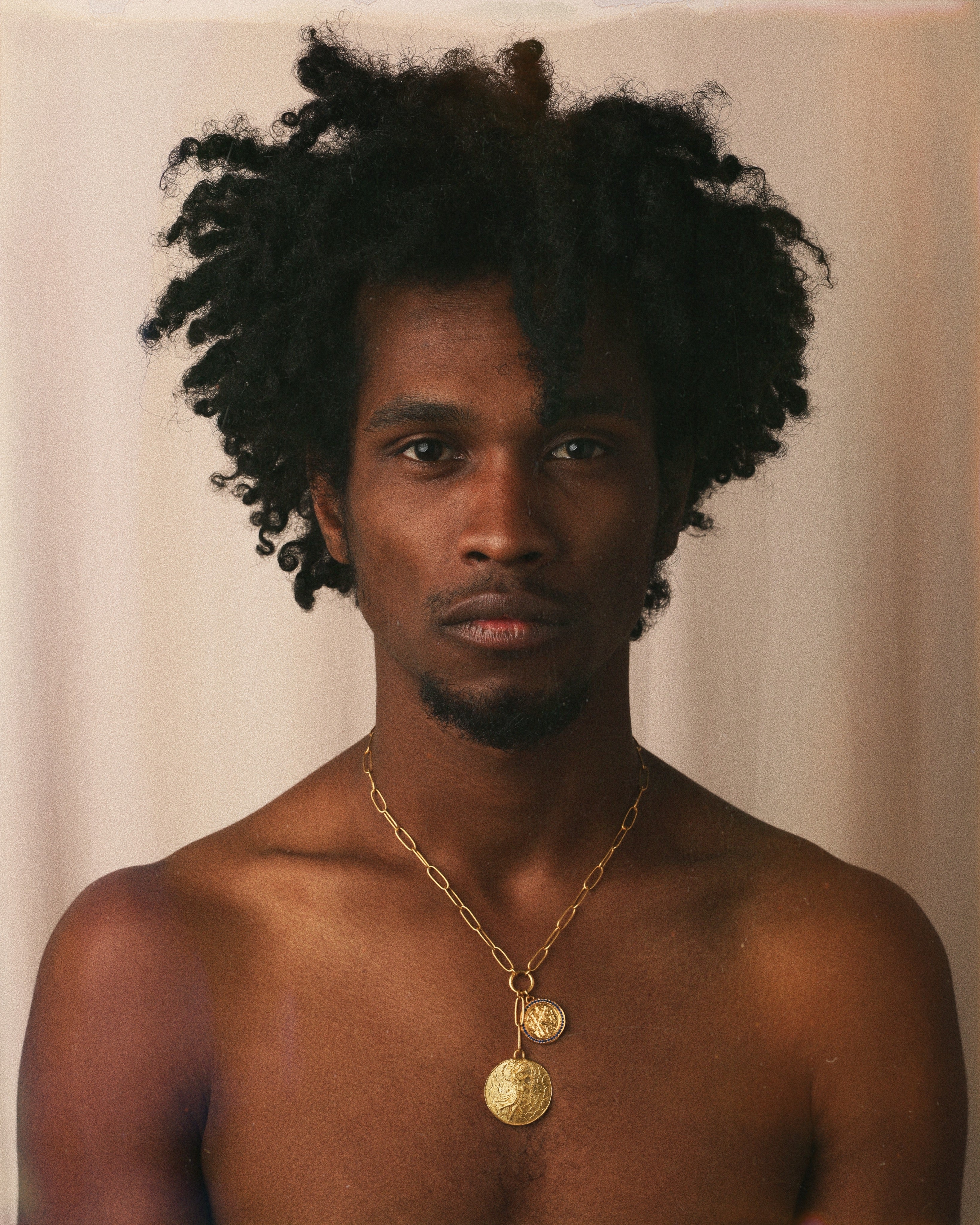

A year down the road, she had settled in and felt ready to move forward— not only with her brand, but with a new found sense of self. “I just felt like, I didn’t work this hard to give up. I was very much inspired, I felt creative again. I felt like I wanted to put campaigns out there that told a new story, maybe a more modern story. People were asking where I had been. People were missing the jewellery and the stories I was telling, so I made it my mission to revamp. It was also kind of a rebirth for me, as a mother and a designer, it was part.”

Sitting across from me, Hakim is confident, centred, and fully claiming her creative freedom and talents. She is also expecting her second baby, due October 2024. Across from me is a person owning their brand and their destiny. “I’m designing pieces that are precious enough and strong enough that I can be proud of again.” Sales reflect that her loyal customers and growing cult-following think so too.

While the Middle East is known for its fine jewellery, Hakim resists the general mindset that the more you spend on diamonds, the more empowered you’ll feel. “I really want to show the world, it's not the value of the stones, the value is in the craftsmanship and how it makes you feel. People like my mother, who would only buy a diamond necklace - or a bride who might take out a loan to buy something to wear for her own wedding - I’m so happy to be a part of the shifting of mindset where you can get 10 times the compliments and feel 10 times more empowered, and you don’t have to break the bank to do it. I really hate the idea of receiving something so precious that if you lose it, you feel like you’ve lost your soul. Jewellery is so emotional, especially like if you’ve received it as an heirloom. And when you lose that, there’s no getting it back. What I like about my jewellery, or what I’m doing, is that the way the jewellery makes you feel is just as - if not more- precious. If you lose the jewellery, it's not the end of the world.”

Reflecting on the past 8 or 9 years growing her brand, she recalls how many people, especially people she never asked, offered her advice or critique. “Or people telling me, how will you ever do this without an investor; you’ll never succeed that way. And now, I’m just so glad that I was able to do it on my own, and I can see - not the finish line - but the future. Today, I find myself transforming from someone who just wanted to be the designer to a designer that’s also a business woman— someone who can take control of their company and make it something global.”

So, what does Alexandra Hakim version 2.0 look like? It is still bold, beautiful and unapologetic. It is beauty as resilience. It's adoration not only for what is delicate, frail and fleeting, but for permanence, strength and stability. Yes- evolving, yes - changing, but staying.

And there’s a new voice being brought to the forefront— “What I want people to realise, is that in the end - the wearer finishes the piece. It's a conversation. My jewellery is a conversation between me and the person wearing it. And it's like tokens of gratitude. You know, you make the piece valuable; its not the other way around. What makes the jewellery valuable is the people who wear it.”